Testing Your App

What you'll learn

- The relationship between Cypress and your back end

- How to configure Cypress to fit your app

- Working with (or without!) your authentication mechanism

- Effectively leveraging test data

Step 1: Start your server

Assuming you've successfully installed Cypress and opened Cypress in your project, the first thing you'll want to do is start your local development server that hosts the application.

It should look something like http://localhost:8080.

Anti-Pattern

Don't try to start a web server from within Cypress scripts. Read about best practices here.

Why start a local development server?

You may be wondering - why can't I just visit my application that's already in production?

While you certainly can test an application that's already deployed, that's not really the sweet spot of Cypress.

Cypress is built, and optimized around being a tool for your daily local development. In fact, after you start using Cypress for awhile, we believe that you may find it useful to even do all of your development in it.

Ultimately you'll not only be able to test and develop at the same time, but you'll actually be able to build your application faster while getting tests "for free".

What's more - since Cypress enables you to do things like stub network requests you can build out your web application without even needing a server to provide valid JSON responses.

Last but not least - trying to shoehorn tests to an already built application is much more difficult than building it as you write tests. You'll likely encounter a series of initial up front challenges / hurdles that would have otherwise been avoided writing tests from the start.

The last, and probably most important reason why you want to test against local servers, is the ability to control them. When your application is running in production you can't control it.

When it's running in development you can:

- take shortcuts

- seed data by running executable scripts

- expose test environment specific routes

- disable security features which make automation difficult

- reset state on the server / database

With that said - you still have the option to have it both ways.

Many of our users run the majority of their integration tests against a local development server, but then reserve a smaller set of smoke tests that run only against a deployed production app.

Step 2: Visit your server

Once your server is running, it's time to visit it.

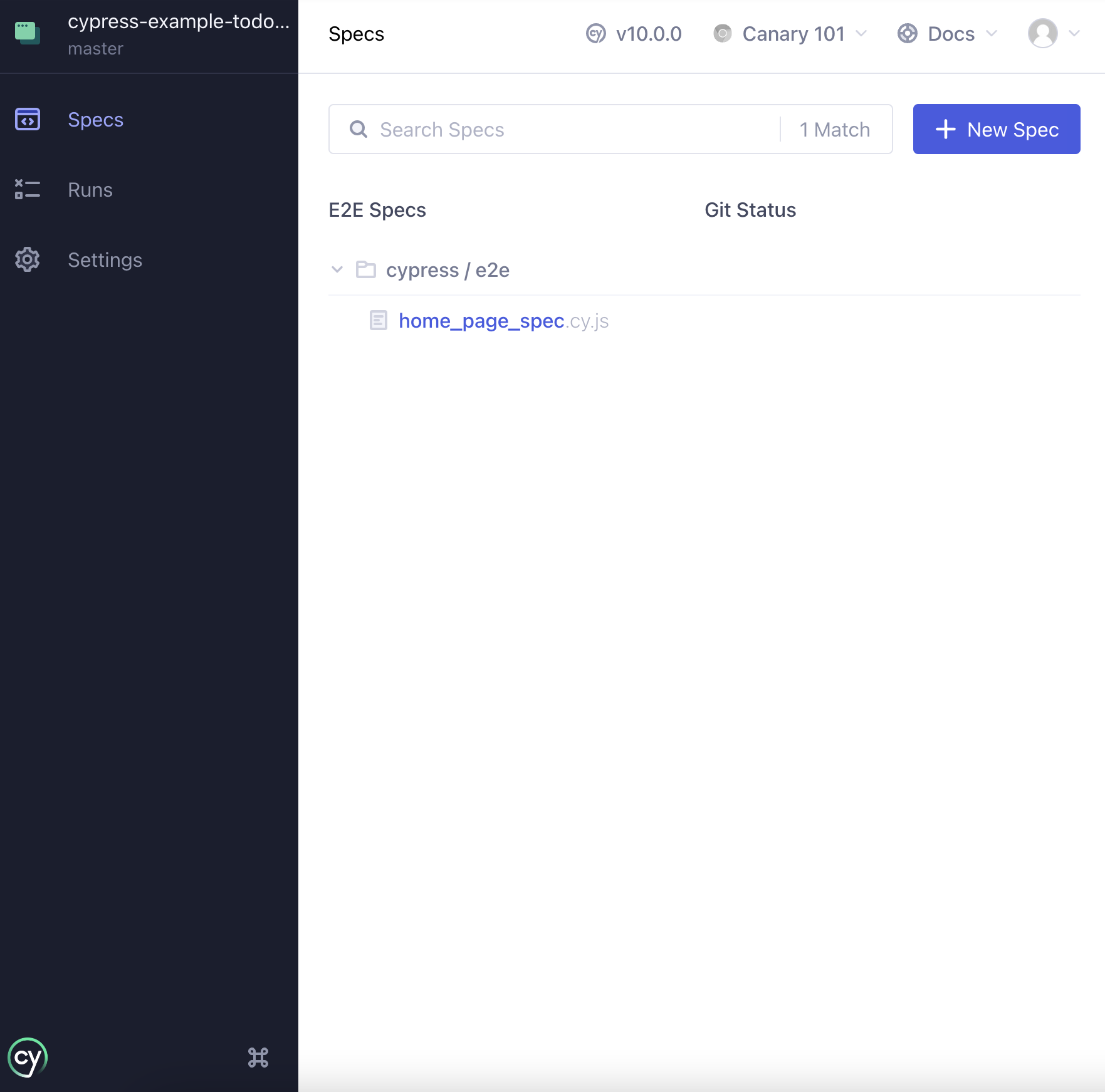

Let's delete the sample.cy.js file created in the previous tutorial now that

it's no longer needed.

rm cypress/e2e/sample.cy.js

Now let's create our own spec file called home_page.cy.js.

touch cypress/e2e/home_page.cy.js

Once that file is created, you should see it in the list of spec files.

Now you'll need to add in the following code in your test file to visit your server:

describe('The Home Page', () => {

it('successfully loads', () => {

cy.visit('http://localhost:8080') // change URL to match your dev URL

})

})

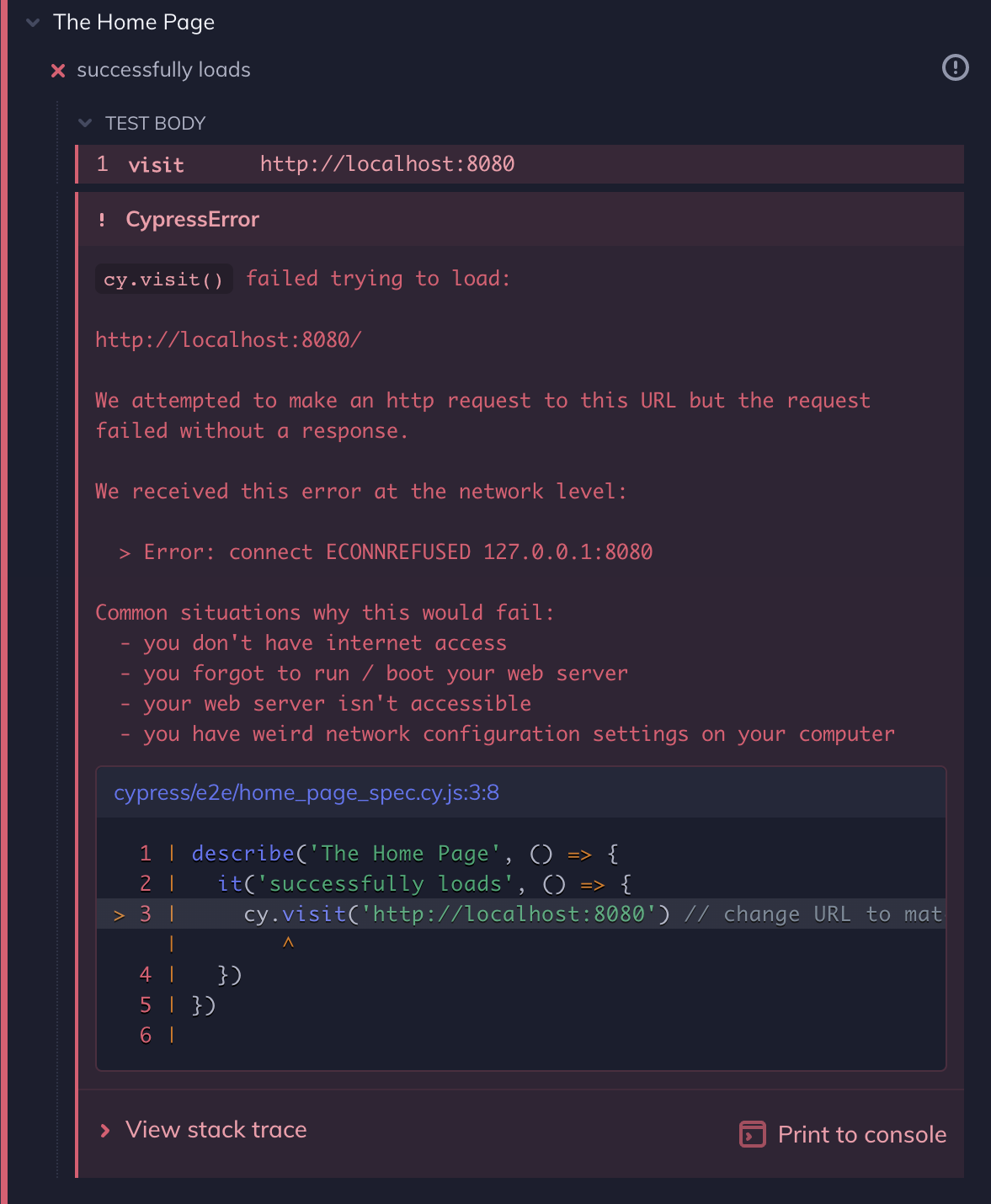

Now click on the home_page.cy.js file and watch Cypress open your browser.

If you forgot to start your server you'll see the error below:

If you've started your server, then you should see your application loaded and working.

Step 3: Configure Cypress

If you think ahead, you'll quickly realize that you're going to be typing this URL a lot, since every test is going to need to visit some page of your application. Luckily, Cypress provides a configuration option for this. Let's leverage that now.

Open up your configuration file. It starts

out empty, but let's add the baseUrl option.

const { defineConfig } = require('cypress')

module.exports = defineConfig({

e2e: {

baseUrl: 'http://localhost:8080'

}

})

import { defineConfig } from 'cypress'

export default defineConfig({

e2e: {

baseUrl: 'http://localhost:8080'

}

})

The cypress.json file has been replaced by cypress.config.js or cypress.config.ts in Cypress version 10.0.0. We recommend

that you update your configuration accordingly.

Please see the new configuration guide and the migration guide for more information.

{

"e2e": {

"baseUrl": "http://localhost:8080"

}

}

This will automatically prefix cy.visit() and

cy.request() commands with this baseUrl.

Whenever you modify your configuration file, Cypress will automatically reboot itself and kill any open browsers. This is normal. Click on the spec file again to relaunch the browser.

We can now visit a relative path and omit the hostname and port.

describe('The Home Page', () => {

it('successfully loads', () => {

cy.visit('/')

})

})

Great! Everything should still be green.

Configuration Options

Cypress has many more configuration options you can use to customize its behavior. Things like where your tests live, default timeout periods, environment variables, which reporter to use, etc.

Check them out in Configuration!

Testing strategies

You're about to embark on writing tests for your application, and only you know your application, so we don't have a lot of specific advice to give you.

What to test, where the edge cases and seams are, what regressions you're likely to run into, etc. are entirely up to you, your application, and your team.

That said, modern web testing has a few wrinkles that every team experiences, so here are some quick tips on common situations you're likely to run into.

Seeding data

Depending on how your application is built - it's likely that your web application is going to be affected and controlled by the server.

Typically these days servers communicate with front end apps via JSON, but you could also be running a traditional server-side rendered HTML web application.

Generally the server is responsible for sending responses that reflect some kind of state it holds - generally in a database.

Traditionally when writing e2e tests using Selenium, before you automate the

browser you do some kind of set up and tear down on the server.

Perhaps you'll need to generate a user, and seed them with associations and records. You may be familiar with using things such as fixtures or factories.

To test various page states - like an empty view, or a pagination view, you'd need to seed the server so that this state can be tested.

While there is a lot more to this strategy, you generally have three ways to facilitate this with Cypress:

cy.exec()- to run system commandscy.task()- to run code in Node via the setupNodeEvents functioncy.request()- to make HTTP requests

If you're running node.js on your server, you might add a before or

beforeEach hook that executes an npm task.

describe('The Home Page', () => {

beforeEach(() => {

// reset and seed the database prior to every test

cy.exec('npm run db:reset && npm run db:seed')

})

it('successfully loads', () => {

cy.visit('/')

})

})

Instead of just executing a system command, you may want more flexibility and could expose a series of routes only when running in a test environment.

For instance, you could compose several requests together to tell your server exactly the state you want to create.

describe('The Home Page', () => {

beforeEach(() => {

// reset and seed the database prior to every test

cy.exec('npm run db:reset && npm run db:seed')

// seed a post in the DB that we control from our tests

cy.request('POST', '/test/seed/post', {

title: 'First Post',

authorId: 1,

body: '...',

})

// seed a user in the DB that we can control from our tests

cy.request('POST', '/test/seed/user', { name: 'Jane' })

.its('body')

.as('currentUser')

})

it('successfully loads', () => {

// this.currentUser will now point to the response

// body of the cy.request() that we could use

// to log in or work with in some way

cy.visit('/')

})

})

While there's nothing really wrong with this approach, it does add a lot of complexity. You will be battling synchronizing the state between your server and your browser - and you'll always need to set up / tear down this state before tests (which is slow).

The good news is that we aren't Selenium, nor are we a traditional e2e testing tool. That means we're not bound to the same restrictions.

With Cypress, there are several other approaches that can offer an arguably better and faster experience.

Stubbing the server

Another valid approach opposed to seeding and talking to your server is to bypass it altogether.

While you'll still receive all of the regular HTML / JS / CSS assets from your

server and you'll continue to cy.visit() it in the same

way - you can instead stub the JSON responses coming from it.

This means that instead of resetting the database, or seeding it with the state we want, you can force the server to respond with whatever you want it to. In this way, we not only prevent needing to synchronize the state between the server and browser, but we also prevent mutating state from our tests. That means tests won't build up state that may affect other tests.

Another upside is that this enables you to build out your application without needing the contract of the server to exist. You can build it the way you want the data to be structured, and even test all of the edge cases, without needing a server.

However - there is likely still a balance here where both strategies are valid (and you should likely do them).

While stubbing is great, it means that you don't have the guarantees that these response payloads actually match what the server will send. However, there are still many valid ways to get around this:

Generate the fixture stubs ahead of time

You could have the server generate all of the fixture stubs for you ahead of time. This means their data will reflect what the server will actually send.

Write a single e2e test without stubs, and then stub the rest

Another more balanced approach is to integrate both strategies. You likely want

to have a single test that takes a true e2e approach and stubs nothing.

It'll use the feature for real - including seeding the database and setting up

state.

Once you've established it's working you can then use stubs to test all of the edge cases and additional scenarios. There are no benefits to using real data in the vast majority of cases. We recommend that the vast majority of tests use stub data. They will be orders of magnitude faster, and much less complex.

Guide: Network Requests

Please read our Guide on Network Requests for a much more thorough analysis and approach to accomplishing this.

Logging in

One of the first (and arguably one of the hardest) hurdles you'll have to overcome in testing is logging into your application.

Nothing slows a test suite down like having to log in, but all the good parts of your application most likely require an authenticated user! Here are some tips.

Fully test the login flow -- but only once!

It's a great idea to get your signup and login flow under test coverage since it is very important to all of your users and you never want it to break.

Logging in is one of those features that are mission critical and should likely involve your server. We recommend you test signup and login using your UI as a real user would:

Here's an example alongside seeding your database:

describe('The Login Page', () => {

beforeEach(() => {

// reset and seed the database prior to every test

cy.exec('npm run db:reset && npm run db:seed')

// seed a user in the DB that we can control from our tests

// assuming it generates a random password for us

cy.request('POST', '/test/seed/user', { username: 'jane.lane' })

.its('body')

.as('currentUser')

})

it('sets auth cookie when logging in via form submission', function () {

// destructuring assignment of the this.currentUser object

const { username, password } = this.currentUser

cy.visit('/login')

cy.get('input[name=username]').type(username)

// {enter} causes the form to submit

cy.get('input[name=password]').type(`${password}{enter}`)

// we should be redirected to /dashboard

cy.url().should('include', '/dashboard')

// our auth cookie should be present

cy.getCookie('your-session-cookie').should('exist')

// UI should reflect this user being logged in

cy.get('h1').should('contain', 'jane.lane')

})

})

You'll likely also want to test your login UI for:

- Invalid username / password

- Username taken

- Password complexity requirements

- Edge cases like locked / deleted accounts

Each of these likely requires a full blown e2e test.

Reusing the login code

At this point there's nothing stopping you copying and pasting the login code

above into every one of your tests that needs an authenticated user. Or you

could even put all your tests in one big spec file and put the login code in a

beforeEach block. But neither of those approaches is particularly

maintainable, and they're certainly not very elegant. A much better solution is

to write a custom cy.login() command.

Custom commands allow you to easily encapsulate and reuse Cypress test logic.

They let you add your own functionality to your test suite and then use it with

the same

chainable and asynchronous API

as the built-in Cypress commands. Lets make the above login example a custom

command and add it to cypress/support/commands.js so it can be leveraged in

any spec file:

// In cypress/support/commands.js

Cypress.Commands.add('login', (username, password) => {

cy.visit('/login')

cy.get('input[name=username]').type(username)

// {enter} causes the form to submit

cy.get('input[name=password]').type(`${password}{enter}`, { log: false })

// we should be redirected to /dashboard

cy.url().should('include', '/dashboard')

// our auth cookie should be present

cy.getCookie('your-session-cookie').should('exist')

// UI should reflect this user being logged in

cy.get('h1').should('contain', username)

})

// In your spec file

it('does something on a secured page', function () {

const { username, password } = this.currentUser

cy.login(username, password)

// ...rest of test

})

Improving performance

You're probably wondering what happened to our advice about logging in "only once". The custom command above will work just fine for testing your secured pages, but if you have more than a handful of tests, logging in before every test is going to increase the overall run time of your suite.

Luckily, Cypress provides the cy.session() command, a

powerful performance tool that lets you cache the browser context associated

with your user and reuse it for multiple tests without going through multiple

login flows! Let's modify the custom cy.login() command from our previous

example to use cy.session():

Cypress.Commands.add('login', (username, password) => {

cy.session(

username,

() => {

cy.visit('/login')

cy.get('input[name=username]').type(username)

cy.get('input[name=password]').type(`${password}{enter}`, { log: false })

cy.url().should('include', '/dashboard')

cy.get('h1').should('contain', username)

},

{

validate: () => {

cy.getCookie('your-session-cookie').should('exist')

},

}

)

})

Third-Party Login

If your app implements login via a third-party authentication provider such as

Auth0 or Okta, you can use the

cy.origin() command to include their login pages as

part of your authentication tests.

There's a lot going on here that's out of the scope for this introduction.

Please check out the cy.session() documentation for a

more in-depth explanation.

Authentication Recipes

Logging in can be more complex than what we've just covered.

We've created several recipes covering additional scenarios like dealing with CSRF tokens or testing XHR based login forms.

Feel free to explore these additional logging in recipes.

Get started

Ok, we're done talking. Now dive in and get started testing your app!

From here you may want to explore some more of our guides:

- Tutorial Videos to watch step-by-step tutorial videos

- Cypress API to learn what commands are available as you work

- Introduction to Cypress explains how Cypress really works

- Command Line for running all your tests outside

via

cypress run - Continuous Integration for running Cypress in CI

- Cross Browser Testing for optimally running tests in CI across Firefox and Chrome-family browsers

- Cypress Real World App (RWA) for practical demonstrations of Cypress testing practices, configuration, and strategies in a real-world project.